A Sermon by Rev. Everett Charters

from November 21, 2021

I come to this sermon painfully aware how much I don’t know about the events we are lamenting tonight.

How much I don’t know about the children, the families, the communities, the nations that were victims of this attempted genocide by our government and our society.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum defines genocide as:

an internationally recognized crime where acts are committed

with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.

These acts fall into five categories:

Killing members of the group

Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group

Deliberately inflicting on the group condition of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group

Forcibly transferring children of that group to another group

That definition chills my soul and to think this is what occurred in this country to Native peoples.

Notice I said Native people, not Native Americans or American Indians.

The majority of words used in the English language to refer to Native peoples have been weaponized.

Indian or worse American Indian is such destructive nomenclature – beginning with the fact that it is nomenclature – the devising or choosing of names for things or for someone – does anyone believe that Native peoples decided to call themselves American Indians?

No, that was something Europeans decided to call them.

To say Native American implies that there was an America before the first Europeans arrived here. There wasn’t.

In our Scripture, to name something is to have dominion over it – remember Genesis 1:26, God gave Adam dominion over and Genesis 2:19 & 20, where Adam was given the power to name everything.

Naming and dominion.

Is it really our God given right to name things? To name people?

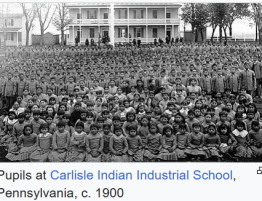

Perhaps the most harmful words spoken with regards to the victims of the boarding schools were “Kill the Indian, save the man.” Words written by Brigadier General Richard Henry Pratt, who opened the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania in 1879, the first government-run boarding school for Native children in the United States and the model upon which the boarding school system would be based.

The reason we called this a service in remembrance of the victims of the Indian Boarding Schools is because that is what they were called by those established them and we used that language because a key part of our lament is recognizing how language was weaponized and used as a tool of genocide.

Native children were punished, even beaten, when they tried to speak their language at the Boarding Schools. As a result, that language was often forgotten, so that when the children finally, were allowed to return home, they often could not speak or understand the language of their families anymore.

Imagine not understanding when your mother or father said, “I love you.” “I’ve missed you.” “Welcome home.”

This is just a part of what we, as white people, carried with us, when we walked into tonight’s service or at any time we attempt to enter into the culture of any of the myriad of tribal communities that are a part of the 574 federally recognized Native nations.

Even that is a term of conquest.

Federally recognized – the federal government decides who is a Native person – a predominantly white federal government.

This is why I know how much I don’t know about the lives of the peoples we are lamenting tonight.

So, what do I know?

I do know that I, that we, try to live each day of our lives as disciples of Jesus.

I know that our Baptismal Covenant is the guide we use to try to live that life.

I know that that Covenant compels us to seek and serve Christ in all persons, to love our neighbors as ourselves, to strive for justice and peace among all people, and to respect the dignity of every human being.

I know that there is one Body and one Spirit; that there is one hope in God’s call to us; that there is One Lord, One Faith, one Baptism, One God and Father of all.

And I know that the fullness of God’s love, and of God’s grace is something beyond humanity’s ability to comprehend and that that love has and continues to reconcile all things that it would otherwise be impossible to.

This is a difficult thing we are doing – listening to and learning the stories of children who were taken away from their families by people who looked like most of us.

There is no way, we alone, can make amends for what has been done to generations of Native peoples.

It is simply beyond our ability to do because we have learned that the wound is too deep.

We are powerless and yet, with God’s help we must still try.

So, we lament.

Lamenting, as we are doing tonight, is a part of learning the truth and about being honest with one another about what has been done.

But lamenting is not static, lamenting is dynamic which means it moves and changes.

Tonight, when we lament, we start in a place of sorrow, of guilt, of misunderstanding, of ignorance.

We lament what we don’t know. And we lament what we have learned.

And then we can begin to move towards another place where we lament for forgiveness but without the expectation of being forgiven.

And we lament not only with words but with actions.

We lament so that we can listen without prejudice to the truth in the lamenting of those who have been harmed. Then, we lament for reconciliation. We lament for what we do not deserve. We lament for the patience to wait with openness. We lament without expectation but we also lament with trust. Trust that our God is a loving God. Trust that Jesus through his life, death, resurrection, and ascension both reconciled and made reconciliation possible.

The Black Lives Matter movement and the work of anti-racism has introduced into our awareness the idea of the ally.

An ally doesn’t lead, an ally supports using their power and their influence in the way that they are told to best use it to fight against racism.

Native peoples don’t need us to tell them how to heal from inter-generational trauma.

They don’t need us to identify their problems for them.

In fact, they don’t need us to tell them anything about their experiences or their needs.

What we can offer, the way we can participate in reconciliation, is to be the ally.

Put our white privilege to work to support the self-identified needs and desires of Native peoples.

In a documentary on the inter-generational trauma of the boarding schools and the enforced removal of Native children from their families, Daniel Nelson Fox, a member of the Wikwemikong First Nation – who was himself taken from his family – talks about the resilience of Native peoples.

After more than 400 years of suffering repeated attempts of genocide, Native peoples, he says, are still here and will always be here.

Native peoples don’t need us to save them.

They aren’t asking us to save them.

They are asking, as so many peoples who have suffered at the hands of white supremacy have, for us to use the power and the privilege we hold as a result of their suffering to dismantle the systems, laws, and institutions that were created for the express purpose of securing white domination over Native peoples. And we don’t have to figure out how to do that.

What we need to do is listen…with humility and then act. We ask, “What needs to change?” and we are told, “This is what needs to change,”

So, we lower our heads, pray to God for strength, and get to work.

This is how we live out our baptismal covenant.

This is how we show we are disciples of Jesus.

This is how we turn lamentation into reconciliation.

See the entire service from Sunday, November 21, 2021 on YouTube here.

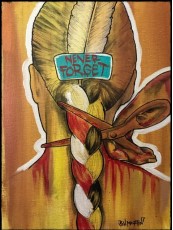

Painting by Bobby Von Martin, Choctaw Nation